Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

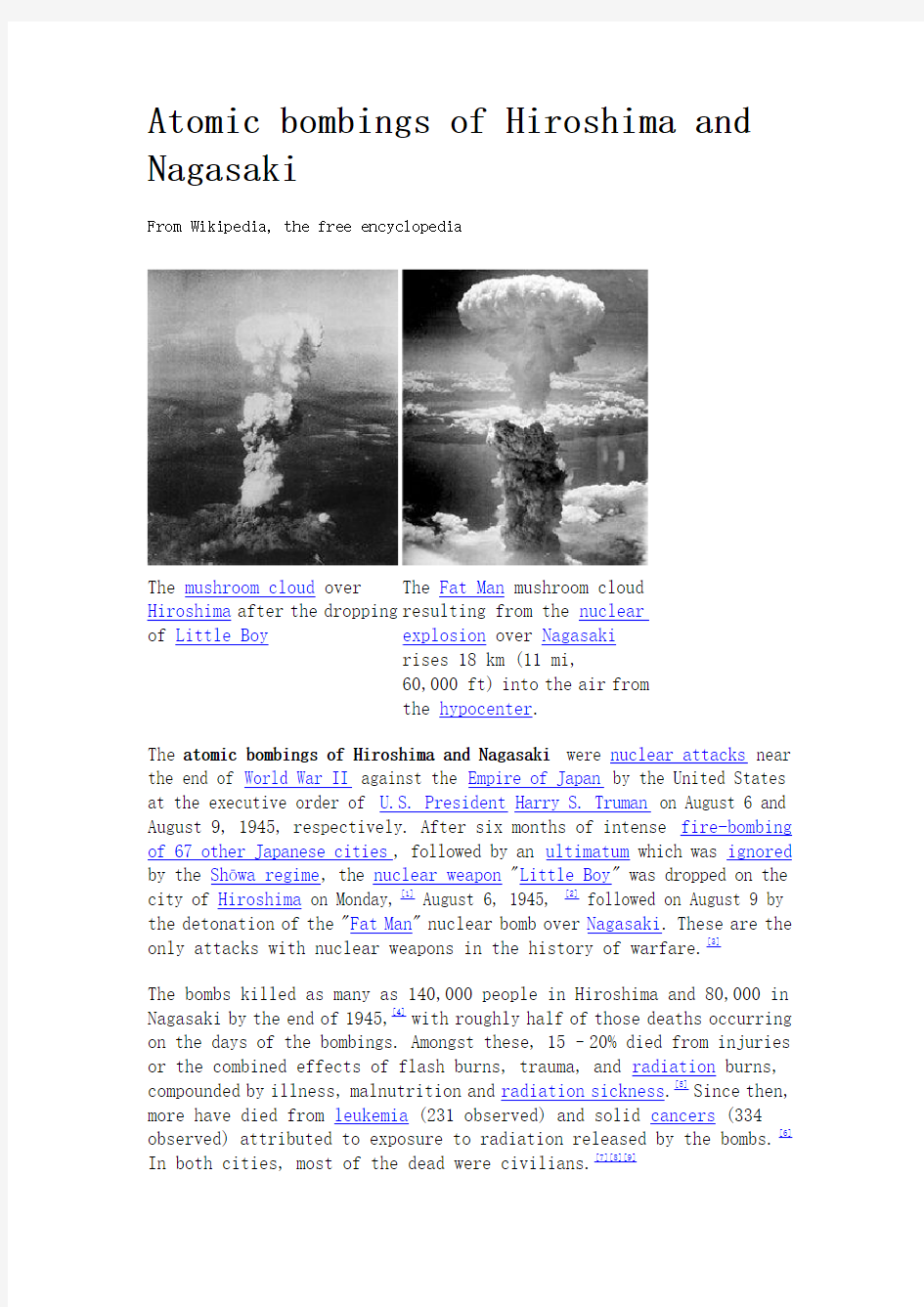

The mushroom cloud over Hiroshima after the dropping of Little Boy The Fat Man mushroom cloud resulting from the nuclear explosion over Nagasaki

rises 18 km (11 mi,

60,000 ft) into the air from

the hypocenter .

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were nuclear attacks near the end of World War II against the Empire of Japan by the United States at the executive order of U.S. President Harry S. Truman on August 6 and August 9, 1945, respectively. After six months of intense fire-bombing of 67 other Japanese cities , followed by an ultimatum which was ignored by the Shōwa regime , the nuclear weapon "Little Boy " was dropped on the city of Hiroshima on Monday,[1] August 6, 1945, [2] followed on August 9 by the detonation of the "Fat Man " nuclear bomb over Nagasaki . These are the

only attacks with nuclear weapons in the history of warfare.[3]

The bombs killed as many as 140,000 people in Hiroshima and 80,000 in Nagasaki by the end of 1945,[4] with roughly half of those deaths occurring on the days of the bombings. Amongst these, 15–20% died from injuries or the combined effects of flash burns, trauma, and radiation burns, compounded by illness, malnutrition and radiation sickness .[5] Since then, more have died from leukemia (231 observed) and solid cancers (334 observed) attributed to exposure to radiation released by the bombs.[6] In both cities, most of the dead were civilians.[7][8][9]

Six days after the detonation over Nagasaki, on August 15, Japan announced its surrender to the Allied Powers, signing the Instrument of Surrender on September 2, officially ending the Pacific War and therefore World War II. (Germany had signed its unavoidable[2]Instrument of Surrender on May 7, ending the war in Europe.) The bombings led, in part, to post-war Japan adopting Three Non-Nuclear Principles, forbidding that nation from nuclear armament.[10]

The Manhattan Project

The United States, in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada, with their respective secret projects Tube Alloys and Chalk River Laboratories,[11][12] designed and built the first atomic bombs under what was called the Manhattan Project. The scientific research was directed by American physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. The Hiroshima bomb, a gun-type bomb called "Little Boy", was made with uranium-235, a rare isotope of uranium. The atomic bomb was first tested at Trinity Site, on July 16, 1945, near Alamogordo, New Mexico. The test weapon, "the gadget," and the Nagasaki bomb, "Fat Man," were both implosion-type devices made primarily of plutonium-239, a synthetic element.[13]

Choice of targets

On May 10–11, 1945 The Target Committee at Los Alamos, led by J. Robert Oppenheimer, recommended Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and the arsenal at Kokura as possible targets. The target selection was subject to the following criteria:

?The target was larger than three miles in diameter and was an important target in a large urban area.

?The blast would create effective damage.

?The target was unlikely to be attacked by August 1945. "Any small and strictly military objective should be located in a much larger area subject to blast damage in order to avoid undue risks of the weapon being lost due to bad placing of the bomb."[14]

These cities were largely untouched during the nightly bombing raids and the Army Air Force agreed to leave them off the target list so accurate assessment of the weapon could be made. Hiroshima was described as "an important army depot and port of embarkation in the middle of an urban industrial area. It is a good radar target and it is such a size that a large part of the city could be extensively damaged. There are adjacent hills which are likely to produce a focussing effect which would considerably increase the blast damage. Due to rivers it is not a good

incendiary target."[14] The goal of the weapon was to convince Japan to surrender unconditionally in accordance with the terms of the Potsdam Declaration. The Target Committee stated that "It was agreed that psychological factors in the target selection were of great importance. Two aspects of this are (1) obtaining the greatest psychological effect against Japan and (2) making the initial use sufficiently spectacular for the importance of the weapon to be internationally recognized when publicity on it is released. In this respect Kyoto has the advantage of the people being more highly intelligent and hence better able to appreciate the significance of the weapon. Hiroshima has the advantage of being such a size and with possible focussing from nearby mountains that a large fraction of the city may be destroyed. The Emperor's palace in Tokyo has a greater fame than any other target but is of least strategic value."[14]

During World War II, Edwin O. Reischauer was the Japan expert for the US Army Intelligence Service, in which role he is incorrectly said to have prevented the bombing of Kyoto.[15] In his autobiography, Reischauer specifically refuted the validity of this broadly-accepted claim:

"...the only person deserving credit for saving Kyoto from destruction is Henry L.

Stimson, the Secretary of War at the time, who had known and admired Kyoto ever since his honeymoon there several decades earlier."[16]

The Potsdam ultimatum

On July 26, Truman and other allied leaders issued the Potsdam Declaration outlining terms of surrender for Japan. It was presented as an ultimatum and stated that without a surrender, the Allies would attack Japan, resulting in "the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland". The atomic bomb was not mentioned in the communique. On July 28, Japanese papers reported that the declaration had been rejected by the Japanese government. That afternoon, Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki declared at a press conference that the Potsdam Declaration was no more than a rehash (yakinaoshi) of the Cairo Declaration and that the government intended to ignore it (mokusatsu lit. "kill by silence").[17] The statement was taken by both Japanese and foreign papers as a clear rejection of the declaration. Emperor Hirohito, who was waiting for a Soviet reply to noncommittal Japanese peace feelers, made no move to change the government position.[18]On July 31, he made clear to his advisor Kōichi Kido that the Imperial Regalia of Japan had to be defended at all costs.[19]

In early July, on his way to Potsdam, Truman had re-examined the decision to use the bomb. In the end, Truman made the decision to drop the atomic bombs on Japan. His stated intention in ordering the bombings was to bring about a quick resolution of the war by inflicting destruction and instilling fear of further destruction in sufficient strength to cause Japan to surrender.[20]

Hiroshima

Hiroshima during World War II

The Enola Gay and its crew, who dropped the "Little Boy" atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

At the time of its bombing, Hiroshima was a city of some industrial and military significance. A number of military camps were located nearby, including the headquarters of the Fifth Division and Field Marshal Shunroku Hata's 2nd General Army Headquarters, which commanded the defense of all of southern Japan. Hiroshima was a minor supply and logistics base for the Japanese military. The city was a communications center, a storage point, and an assembly area for troops. It was one of several Japanese cities left deliberately untouched by American bombing, allowing a pristine environment to measure the damage caused by the atomic bomb.[citation needed]

The center of the city contained several reinforced concrete buildings and lighter structures. Outside the center, the area was congested by a dense collection of small wooden workshops set among Japanese houses. A few larger industrial plants lay near the outskirts of the city. The houses were constructed of wood with tile roofs, and many of the industrial buildings were also built around wood frames. The city as a whole was highly susceptible to fire damage.

The population of Hiroshima had reached a peak of over 381,000 earlier in the war, but prior to the atomic bombing the population had steadily decreased because of a systematic evacuation ordered by the Japanese government. At the time of the attack the population was approximately 340,000-350,000.[4] Because official documents were burned, the exact population is uncertain.

The bombing

For the composition of the USAAF mission see 509th Composite Group.

Seizo Yamada's ground level photo taken from approximately 7 km northeast of Hiroshima.

Hiroshima was the primary target of the first nuclear bombing mission on August 6, with Kokura and Nagasaki being alternative targets. August 6 was chosen because clouds had previously obscured the target. The 393d Bombardment Squadron B-29Enola Gay, piloted and commanded by 509th Composite Group commander Colonel Paul Tibbets, was launched from North Field airbase on Tinian in the West Pacific, about six hours flight time from Japan. The Enola Gay (named after Colonel Tibbets' mother) was accompanied by two other B29s. The Great Artiste, commanded by Major Charles W. Sweeney, carried instrumentation; and a then-nameless aircraft later called Necessary Evil (the photography aircraft) was commanded by Captain George Marquardt.[21]

After leaving Tinian the aircraft made their way separately to Iwo Jima where they rendezvoused at 2,440 meters (8,000 ft) and set course for Japan. The aircraft arrived over the target in clear visibility at 9,855 meters (32,330 ft). During the journey, Navy Captain William Parsons had armed the bomb, which had been left unarmed to minimize the

risks during takeoff. His assistant, 2nd Lt. Morris Jeppson, removed the safety devices 30 minutes before reaching the target area.[22]

About an hour before the bombing, Japanese early warning radar detected the approach of some American aircraft headed for the southern part of Japan. An alert was given and radio broadcasting stopped in many cities, among them Hiroshima. At nearly 08:00, the radar operator in Hiroshima determined that the number of planes coming in was very small—probably not more than three—and the air raid alert was lifted. To conserve fuel and aircraft, the Japanese had decided not to intercept small formations. The normal radio broadcast warning was given to the people that it might be advisable to go to air-raid shelters if B-29s were actually sighted, but no raid was expected beyond some sort of reconnaissance.

The energy released was powerful enough to burn through clothing. The dark portions of the garments this victim wore at the time of the blast were emblazoned on to the flesh as scars.[23]

The release at 08:15 (Hiroshima time) went as planned, and the gravity bomb known as "Little Boy", a gun-type fission weapon with 60 kilograms (130 lb) of uranium-235, took 57 seconds to fall from the aircraft to the predetermined detonation height about 600 meters (2,000 ft) above the city. Due to crosswind, it missed the aiming point, the Aioi Bridge, by almost 800 feet (240 m) and detonated directly over Shima Surgical Clinic.[24] It created a blast equivalent to about 13 kilotons of TNT (54 TJ). (The U-235 weapon was considered very inefficient, with only 1.38% of its material fissioning.)[25]The radius of total destruction was about one mile (1.6 km), with resulting fires across 4.4 square miles (11 km2).[26]Americans estimated that 4.7 square miles (12 km2) of the city were destroyed. Japanese officials determined that 69% of Hiroshima's buildings were destroyed and another 6–7% damaged.[5]

70,000–80,000 people, or some 30%[27]of the population of Hiroshima were killed immediately, and another 70,000 injured.[28]Over 90% of the doctors and 93% of the nurses in Hiroshima were killed or injured—most had been in the downtown area which received the greatest damage.[29]

Although the United States had previously dropped leaflets warning civilians of air raids on twelve other Japanese cities,[30] the residents of Hiroshima were given no notice of the atomic bomb.[31][32][33]

Japanese realization of the bombing

Hiroshima before the bombing. Hiroshima after the bombing. The Tokyo control operator of the Japanese Broadcasting Corporation noticed that the Hiroshima station had gone off the air. He tried to re-establish his program by using another telephone line, but it too had failed.[34] About twenty minutes later the Tokyo railroad telegraph center realized that the main line telegraph had stopped working just north of Hiroshima. From some small railway stops within 16 kilometers (10 mi) of the city came unofficial and confused reports of a terrible explosion in Hiroshima. All these reports were transmitted to the headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff .

Military bases repeatedly tried to call the Army Control Station in Hiroshima. The complete silence from that city puzzled the men at

headquarters; they knew that no large enemy raid had occurred and that no sizeable store of explosives was in Hiroshima at that time. A young officer of the Japanese General Staff was instructed to fly immediately to Hiroshima, to land, survey the damage, and return to Tokyo with reliable information for the staff. It was generally felt at headquarters that nothing serious had taken place and that the explosion was just a rumor. The staff officer went to the airport and took off for the southwest. After flying for about three hours, while still nearly one hundred miles (160 km) from Hiroshima, he and his pilot saw a great cloud of smoke from the bomb. In the bright afternoon, the remains of Hiroshima were burning. Their

plane soon reached the city, around which they circled in disbelief. A great scar on the land still burning and covered by a heavy cloud of smoke was all that was left. They landed south of the city, and the staff officer, after reporting to Tokyo, immediately began to organize relief measures.

By August 8, 1945, newspapers in the US were reporting that broadcasts from Radio Tokyo had described the destruction observed in Hiroshima. "Practically all living things, human and animal, were literally seared to death," Japanese radio announcers said in a broadcast captured by Allied sources.[35]

Post-attack casualties

According to most estimates, the immediate effects of the blast killed approximately 70,000 people in Hiroshima. Estimates of total deaths by the end of 1945 from burns, radiation and related disease, the effects of which were aggravated by lack of medical resources, range from 90,000 to 140,000.[4][36] Some estimates state up to 200,000 had died by 1950, due to cancer and other long-term effects.[1][7][37]Another study states that from 1950 to 1990, roughly 9% of the cancer and leukemia deaths among bomb survivors was due to radiation from the bombs, the statistical excess being estimated to 89 leukemia and 339 solid cancers.[38] At least eleven known prisoners of war died from the bombing.[39]

Survival of some structures

Small-scale recreation of the Nakajima area around ground zero.

Some of the reinforced concrete buildings in Hiroshima had been very strongly constructed because of the earthquake danger in Japan, and their framework did not collapse even though they were fairly close to the blast center. Eizo Nomura (野村英三Nomura Eizō?) was the closest known survivor, who was in the basement of a modern "Rest House" only 100 m (330 ft) from ground-zero at the time of the attack.[40]Akiko Takakura (高

蔵信子Takakura Akiko?) was among the closest survivors to the hypocenter of the blast. She had been in the solidly built Bank of Hiroshima only 300 meters (980 ft) from ground-zero at the time of the attack.[41] Since the bomb detonated in the air, the blast was directed more downward than sideways, which was largely responsible for the survival of the Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall, now commonly known as the Genbaku, or A-bomb Dome. This building was designed and built by the Czech architect Jan Letzel, and was only 150 m (490 ft) from ground zero (the hypocenter). The ruin was named Hiroshima Peace Memorial and was made a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996 over the objections of the U.S. and China.[42]

Events of August 7-9

After the Hiroshima bombing, President Truman announced, if they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air the likes of which has never been seen on this earth.

The Japanese government still did not react to the Potsdam Declaration. Emperor Hirohito, the government, and the war council were considering four conditions for surrender: the preservation of the kokutai(Imperial institution and national polity), assumption by the Imperial Headquarters of responsibility for disarmament and demobilization, no occupation of the Japanese Home Islands, Korea, or Formosa, and delegation of the punishment of war criminals to the Japanese government.[43]

The Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov had informed Tokyo of the Soviet Union's unilateral abrogation of the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact on April 5. At two minutes past midnight on August 9, Tokyo time, Soviet infantry, armor, and air forces had launched the Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation. Four hours later, word reached Tokyo that the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan. The senior leadership of the Japanese Army began preparations to impose martial law on the nation, with the support of Minister of War Korechika Anami, in order to stop anyone attempting to make peace.

Responsibility for the timing of the second bombing was delegated to Colonel Tibbets as commander of the 509th Composite Group on Tinian. Scheduled for August 11 against Kokura, the raid was moved earlier by two days to avoid a five day period of bad weather forecast to begin on August 10.[44] Three bomb pre-assemblies had been transported to Tinian, labeled F-31, F-32, and F-33 on their exteriors. On August 8, a dress rehearsal was conducted off Tinian by Maj. Charles Sweeney using Bockscar as the drop airplane. Assembly F-33 was expended testing the components and F-31 was designated for the August 9 mission.[45]

Nagasaki

Nagasaki during World War II

The Bockscar and its crew, who dropped the "Fat Man" atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

The city of Nagasaki had been one of the largest sea ports in southern Japan and was of great wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity, including the production of ordnance, ships, military equipment, and other war materials.

In contrast to many modern aspects of Hiroshima, almost all of the buildings were of old-fashioned Japanese construction, consisting of wood or wood-frame buildings with wood walls (with or without plaster) and tile roofs. Many of the smaller industries and business establishments were also situated in buildings of wood or other materials not designed to withstand explosions. Nagasaki had been permitted to grow for many years without conforming to any definite city zoning plan; residences were erected adjacent to factory buildings and to each other almost as closely as possible throughout the entire industrial valley.

Nagasaki had never been subjected to large-scale bombing prior to the explosion of a nuclear weapon there. On August 1, 1945, however, a number of conventional high-explosive bombs were dropped on the city. A few hit in the shipyards and dock areas in the southwest portion of the city, several hit the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, and six bombs landed at the Nagasaki Medical School and Hospital, with three direct hits on buildings there. While the damage from these bombs was relatively small, it created considerable concern in Nagasaki and many people—principally school children—were evacuated to rural areas for safety, thus reducing the population in the city at the time of the nuclear attack.

To the north of Nagasaki there was a camp holding British Commonwealth prisoners of war, some of whom were working in the coal mines and only found out about the bombing when they came to the surface. At least eight known POWs died from the bombing and as many as thirteen POWs may have died:

?One British Commonwealth citizen[46][47][48][49][50]

?Seven Dutch POWs (two names known)[51] died in the bombing.

?At least two POWs reportedly died postwar from cancer thought to have been caused by the atomic bomb.[52][53]

The bombing

For the composition of the USAAF mission see 509th Composite Group.

A post-war "Fat Man" model.

On the morning of August 9, 1945, the U.S. B-29 Superfortress Bockscar, flown by the crew of 393rd Squadron commander Major Charles W. Sweeney, carried the nuclear bomb code-named "Fat Man", with Kokura as the primary target and Nagasaki the secondary target. The mission plan for the second attack was nearly identical to that of the Hiroshima mission, with two B-29s flying an hour ahead as weather scouts and two additional B-29s in Sweeney's flight for instrumentation and photographic support of the mission. Sweeney took off with his weapon already armed but with the electrical safety plugs still engaged.[54]

Observers aboard the weather planes reported both targets clear. When Sweeney's aircraft arrived at the assembly point for his flight off the coast of Japan, the third plane, Big Stink, flown by the group's Operations Officer, Lt. Col. James I. Hopkins, Jr. failed to make the rendezvous. Bockscar and the instrumentation plane circled for forty minutes without locating Hopkins. Already 30 minutes behind schedule, Sweeney decided to fly on without Hopkins.[54]

Nagasaki before and after bombing.

By the time they reached Kokura a half hour later, a 70% cloud cover had obscured the city, prohibiting the visual attack required by orders. After three runs over the city, and with fuel running low because a transfer pump on a reserve tank had failed before take-off, they headed for their secondary target, Nagasaki.[54]Fuel consumption calculations made en route indicated that Bockscar had insufficient fuel to reach Iwo Jima and would be forced to divert to Okinawa. After initially deciding that if Nagasaki were obscured on their arrival the crew would carry the bomb to Okinawa and dispose of it in the ocean if necessary, the weaponeer Navy Commander Frederick Ashworth decided that a radar approach would be used if the target was obscured.[55]

At about 07:50 Japanese time, an air raid alert was sounded in Nagasaki, but the "all clear" signal was given at 08:30. When only two B-29 Superfortresses were sighted at 10:53, the Japanese apparently assumed that the planes were only on reconnaissance and no further alarm was given.

A few minutes later at 11:00, The Great Artiste, the support B-29 flown by Captain Frederick C. Bock, dropped instruments attached to three parachutes. These instruments also contained an unsigned letter to Professor Ryokichi Sagane, a nuclear physicist at the University of Tokyo who studied with three of the scientists responsible for the atomic bomb at the University of California, Berkeley, urging him to tell the public about the danger involved with these weapons of mass destruction. The messages were found by military authorities but not turned over to Sagane until a month later.[56] In 1949 one of the authors of the letter, Luis Alvarez, met with Sagane and signed the document.[57]

A Japanese report on the bombing characterized Nagasaki as "like a graveyard with not a tombstone standing".

At 11:01, a last minute break in the clouds over Nagasaki allowed Bockscar's bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan, to visually sight the target as ordered. The "Fat Man" weapon, containing a core of ~6.4 kg (14.1 lbs.) of plutonium-239, was dropped over the city's industrial valley. Forty-three seconds later it exploded 469 meters (1,540 ft) above

the ground exactly halfway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works (Torpedo Works) in the north. This was nearly 3 kilometers (2 mi) northwest of the planned hypocenter; the blast was confined to the Urakami Valley and a major portion of the city was protected by the intervening hills.[58] The resulting explosion had a blast yield equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT (88 TJ).[citation needed]The explosion generated heat estimated at 3,900 degrees Celsius (4,200 K, 7,000 °F) and winds that were estimated at 1005 km/h (624 mph).

Casualty estimates for immediate deaths range from 40,000 to 75,000.[59][60][61] Total deaths by the end of 1945 may have reached 80,000.[4] The radius of total destruction was about a mile (1–2 km), followed by fires across the northern portion of the city to two miles (3 km) south of the bomb.[62][63]

An unknown number of survivors from the Hiroshima bombing had made their way to Nagasaki, where they were bombed again.[64][65]

The Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works, the factory that manufactured the type 91 torpedoes released in Pearl Harbor, was subsequently destroyed in the blast.[66]

Plans for more atomic attacks on Japan

The United States expected to have another atomic bomb ready for use in the third week of August, with three more in September and a further three in October.[67]On August 10, Major General Leslie Groves, military director of the Manhattan Project, sent a memorandum to General of the Army George Marshall, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, in which he wrote that "the next bomb . . should be ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17 or August 18." On the same day, Marshall endorsed the memo with the comment, "It is not to be released over Japan without express authority from the President."[67]There was already discussion in the War Department about conserving the bombs in production until Operation Downfall, the projected invasion of Japan, had begun. "The problem now [August 13] is whether or not, assuming the Japanese do not capitulate, to continue dropping them every time one is made and shipped out there or whether to hold them . . . and then pour them all on in a reasonably short time. Not all in one day, but over a short period. And that also takes into consideration the target that we are after. In other words, should we not concentrate on targets that will be of the greatest assistance to an invasion rather than industry, morale, psychology, and the like? Nearer the tactical use rather than other use."[67]

The surrender of Japan and subsequent occupation Main articles: Surrender of Japan and Occupation of Japan

Until August 9, the war council had still insisted on its four conditions for surrender. On that day Hirohito ordered Kido to "quickly control the situation ... because the Soviet Union has declared war against us." He then held an Imperial conference during which he authorized minister Tōgōto notify the Allies that Japan would accept their terms on one condition, that the declaration "does not compromise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign ruler."[68]

On August 12, the Emperor informed the imperial family of his decision to surrender. One of his uncles, Prince Asaka, then asked whether the war would be continued if the kokutai could not be preserved. Hirohito simply replied "of course."[69] As the Allied terms seemed to leave intact the principle of the preservation of the Throne, Hirohito recorded on August 14 his capitulation announcement which was broadcast to the Japanese nation the next day despite a short rebellion by militarists opposed to the surrender.

In his declaration, Hirohito referred to the atomic bombings: “Moreover, the enemy now possesses a new and terrible weapon with the power to destroy many innocent lives and do incalculable damage. Should we continue to

fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese

nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.

Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our

subjects, or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of

Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered

the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of

the Powers. ”

In his "Rescript to the soldiers and sailors" delivered on August 17, he stressed the impact of the Soviet invasion and his decision to surrender, omitting any mention of the bombs.

During the year after the bombing, approximately 40,000 U.S. troops occupied Hiroshima, while Nagasaki was occupied by 27,000 troops.

Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission

In the spring of 1948, the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) was established in accordance with a presidential directive from Harry S. Truman to the National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council to conduct investigations of the late effects of radiation among the survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Among the casualties were found many unintended victims, including Allied POWs, Korean and Chinese laborers, students from Malaya on scholarships, and some 3,200 Japanese American citizens.[70]

One of the early studies conducted by the ABCC was on the outcome of pregnancies occurring in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and in a control city, Kure located 18 miles (29 km) south from Hiroshima, in order to discern the conditions and outcomes related to radiation exposure. Some claimed ABCC was not in a position to offer medical treatment to the survivors except in a research capacity.[who?] One author has claimed that the ABCC refused to provide medical treatment to the survivors for better research results.[71]In 1975, the Radiation Effects Research Foundation was created to assume the responsibilities of ABCC. [72]

The hibakusha

Main article: hibakusha

Panoramic view of the monument marking the hypocenter, or ground zero, of the atomic bomb explosion over Nagasaki.

Citizens of Hiroshima walk by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, the closest building to have survived the city's atomic bombing.

The surviving victims of the bombings are called hibakusha (被爆者?), a Japanese word that literally translates to "explosion-affected people." The suffering caused by the bombing has led Japan to seek the abolition of nuclear weapons from the world ever since, exhibiting one of the world's firmest non-nuclear policies. As of March 31, 2009, 235,569 hibakusha were recognized by the Japanese government, most living in Japan.[73] The government of Japan recognizes about 1% of these as having illnesses caused by radiation.[74] The memorials in Hiroshima and Nagasaki contain lists of the names of the hibakusha who are known to have died since the bombings. Updated annually on the anniversaries of the bombings, as of August 2009 the memorials record the names of more than 410,000 hibakusha—263,945[75] in Hiroshima and 149,226[76] in Nagasaki.

Korean survivors

During the war, Japan brought many Korean conscripts to both Hiroshima and Nagasaki to work as forced labor. According to recent estimates, about 20,000 Koreans were killed in Hiroshima and about 2,000 died in Nagasaki. It is estimated that one in seven of the Hiroshima victims was of Korean ancestry.[8] For many years, Koreans had a difficult time fighting for recognition as atomic bomb victims and were denied health benefits. However, most issues have been addressed in recent years through lawsuits.[77]

Double survivor

Main article: Tsutomu Yamaguchi

On March 24, 2009, the Japanese government recognized Tsutomu Yamaguchi as a double hibakusha. Tsutomu Yamaguchi was confirmed to be 3 kilometers from ground zero in Hiroshima on a business trip when the bomb was detonated. He was seriously burnt on his left side and spent the night

in Hiroshima. He got back to his home city of Nagasaki on August 8, a day before the bomb in Nagasaki was dropped, and he was exposed to residual radiation while searching for his relatives. He is the first confirmed survivor of both bombings.[78]

Debate over bombings

Main article: Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Further information: Operation Downfall

“The atomic bomb was more than a weapon of terrible destruction; it was a psychological weapon.”

— Former U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, 1947[79]

The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender and the United States' ethical justification for them has been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades. J. Samuel Walker wrote in an April 2005 overview of recent historiography on the issue, "the controversy over the use of the bomb seems certain to continue." Walker noted that "The fundamental issue that has divided scholars over a period of nearly four decades is whether the use of the bomb was necessary to achieve victory in the war in the Pacific on terms satisfactory to the United States."[80] Supporters of the bombings generally assert that they caused the Japanese surrender, preventing massive casualties on both sides in the planned invasion of Japan: Kyūshū was to be invaded in October 1945 and Honshūfive months later. Some estimate Allied forces would have suffered 1 million casualties in such a scenario, while Japanese casualties would have been in the millions.[81] Others who oppose the bombings argue that it was simply an extension of the already fierce conventional bombing campaign[82]and, therefore, militarily unnecessary,[83]inherently immoral, a war crime, or a form of state terrorism.[84]

Hiroshima课文

Hiroshima ---- The "Liveliest" City in Japan (excerpts) by Jacques Danvoir “Hiroshima! Everybody off!” That must be what the man in the Japanese stationmaster's uniform shouted, as the fastest train in the world slipped to a stop in Hiroshima Station. I did not understand what he was saying. First of all, because he was shouting in Japanese. And secondly, because I had a lump in my throat and a lot of sad thoughts on my mind that had little to do with anything a Nippon railways official might say. The very act of stepping on this soil, in breathing this air of Hiroshima, was for me a far greater adventure than any trip or any reportorial assignment I'd previously taken. Was I not at the scene of the crime? The Japanese crowd did not appear to have the same preoccupations that I had. From the sidewalk outside the station, things seemed much the same as in other Japanese cities. Little girls and elderly ladies in kimonos rubbed shoulders with teenagers and women in western dress. Serious looking men spoke to one another as if they were oblivious of the crowds about them, and bobbed up and down repeatedly in little bows, as they exchanged the ritual formula of gratitude and respect: "Tomo aligato gozayimas." Others were using little red telephones that hung on the facades of grocery stores and tobacco shops. "Hi! Hi!" said the cab driver, whose door popped open at the very sight of a traveler. "Hi", or something that sounds very much like it, means "yes". "Can you take me to City Hall?" He grinned at me in the rear-view mirror and repeated "Hi!" "Hi! ’ We se t off at top speed through the narrow streets of

Hiroshima -- the Liveliest” city in Japan

“Hiroshima! Everybody off!” That must be what the man in the Japanese stationmaster's uniform shouted, as the fastest train in the world slipped to a stop in Hiroshima Station. I did not understand what he was saying. First of all, because he was shouting in Japanese. And secondly, because I had a lump in my throat and a lot of sad thoughts on my mind that had little to do with anything a Nippon railways official might say. The very act of stepping on this soil, in breathing this air of Hiroshima, was for me a far greater adventure than any trip or any reportorial assignment I'd previously taken. Was I not at the scene of the crime? The Japanese crowd did not appear to have the same "Hi! Hi!" said the cab driver, whose door Just as I was beginning to find the ride long, the taxi screeched to a halt, and the driver got out and went over to a policeman to ask the way. As in Tokyo, taxi drivers in Hiroshima often know little of their city, but to avoid loss of face before foreigners, will not admit their ignorance, and will accept any destination without concern for how long it may take them to find it. At last this Thanks to his map, I was able to find a taxi driver who could take me straight to the canal At the door to the restaurant, a He was a tall, thin man, sad-eyed and serious. Quite unexpectedly, the strange emotion which had overwhelmed me at the station returned, and I was again The introductions were made. Most of the guests were Japanese, and it was difficult for me to ask them just why we were gathered here. The few Americans and Germans seemed just as Everyone bowed, including the Westerners. After three days in Japan, the "Gentlemen, it is a very great honor to have you her e in Hiroshima." There were fresh bows, and the faces grew more and more serious each time the name Hiroshima was repeated. "Hiroshima, as you know, is a city familiar to everyone,” continued the mayor. "Yes, yes, of course,” murmured the company, more and more "Seldom has a city gained such world I was just about to make my little bow of "Hiroshima – oysters? What about the bomb and the misery and humanity's most

Hiroshima英文赏析

Hiroshima ―the“Liveliest”City in Japan Hiroshima ―the“Liveliest”City in Japan is a radio report which describes the author’s experience visited the first city suffered from the atomic bomb in the world——Hiroshima. The story beginning with the author’s arrival at the railway station .The author does not try to conceal his emotions about the city or his attitude toward the atomic bomb. In the very first paragraph he says , “I had a lump in my throat and a lot of sad thoughts on my mind.”He asked, “Was I not at the scene of the crime?” On his way to his destination he observed the crowds of Japanese. At the reception, the author excepted the mayor to talk about the atomic bomb and its tragic impact. To his great surprise, the mayor referred to Hiroshima as the “Liveliest city in Japan.”The puzzled author was told by an elderly Japanese man that there were two schools of thought in Hiroshima about the bomb. With many prepared questions, the author visited the atomic bomb victims and came to his conclusion about Hiroshima. From this whole passage, we can know the main idea of this story is about the dual characters of Hiroshima, the coexistence of liveliness and bidden pains, the result of the nuclear bombardment. Besides, the theme that the author wanted to express is obvious. It tells us that even though some Japanese try their best to forget the humiliating past and construct a new and energetic city, but history is

英语专业大三上学期高级英语课文翻译第二课Hiroshima-the_livest_city_in_Japan

第二课 广岛——日本“最有活力”的城市雅各?丹瓦“广岛到了!大家请下车!”当 世界上最快的高速列车减速驶进广岛车站并渐渐停稳时,那位身着日本火车站站长制服的男人口中喊出的一定是这样的话。我其实并没有听懂他在说些什么,一是因为他是用日语喊的,其次,则是因为我当时心情沉重,喉咙哽噎,忧思万缕,几乎顾不上去管那日本铁路官员说些什么。踏上这块土地,呼吸着广岛的空气,对我来说这行动本身已是一套令人激动的经历,其意义远远超过我以往所进行的任何一次旅行或采访活动。难道我不就是在犯罪现场吗? 这儿的日本人看来倒没有我这样的忧伤情绪。从车站外的人行道上看去,这儿的一切似乎都与日本其他城市没什么两样。身着和嘏的小姑娘和上了年纪的太太与西装打扮的少年和妇女摩肩接豫;神情严肃的男人们对周围的人群似乎视而不见,只顾着相互交淡,并不停地点头弯腰,互致问候:“多么阿里伽多戈扎伊马嘶。”还有人在使用杂货铺和烟草店门前挂着的小巧的红色电话通话。 “嗨!嗨!”出租汽车司机一看见旅客,就砰地打开车门,这样打着招呼。“嗨”,或者某个发音近似“嗨”的什么词,意思是“对”或“是”。“能送我到市政厅吗?”司机对着后视镜冲我一笑,又连声“嗨!”“嗨!”出租车穿过广岛市区狭窄的街巷全速奔驰,我们的身子随着司机手中方向盘的一次次急转而前俯后仰,东倒西歪。与此同时,这座曾惨遭劫难的城市的高楼大厦则一座座地从我们身边飞掠而过。 正当我开始觉得路程太长时,汽车嘎地一声停了下来,司机下车去向警察问路。就像东京的情形一样,广岛的出租车司机对他们所在的城市往往不太熟悉,但因为怕在外国人面前丢脸,却又从不肯承认这一点。无论乘客指定的目的地在哪里,他们都毫不犹豫地应承下来,根本不考虑自己要花多长时间才能找到目的地。 这段小插曲后来终于结束了,我也就不知不觉地突然来到了宏伟的市政厅大楼前。当我出示了市长应我的采访要求而发送的请柬后,市政厅接待人员向我深深地鞠了一躬,然后声调悠扬地长叹了一口气。 “不是这儿,先生,”他用英语说道。“市长邀请您今天晚上同其他外宾一起在水上餐厅赴宴。您看,就是这儿。”他边说边为我在请柬背面勾划出了一张简略的示意图。 幸亏有了他画的图,我才找到一辆出租车把我直接送到了运河堤岸,那儿停泊着一艘顶篷颇像一般日本房屋屋顶的大游艇。由于地价过于昂贵,日本人便把传统日本式房屋建到了船上。漂浮在水面上的旧式日本小屋夹在一座座灰黄色摩天大楼之间,这一引人注目的景观正象征着和服与超短裙之间持续不断的斗争。 在水上餐厅的门口,一位身着和服、面色如玉、风姿绰约的迎宾女郎告诉我要脱鞋进屋。于是我便脱下鞋子,走进这座水上小屋里的一个低矮的房间,蹑手蹑脚地踏在柔软的榻榻米地席上,因想到要这样穿着袜子去见广岛市长而感到十分困窘不安。 市长是位瘦高个儿的男人,目光忧郁,神情严肃。出人意料的是,刚到广岛车站时袭扰着我的那种异样的忧伤情绪竟在这时重新袭上心头,我的心情又难受起来,因为我又一次意识到自己置身于曾遭受第一颗原子弹轰击的现场。这儿曾有成千上万的生命顷刻之间即遭毁灭,还有成千上万的人在痛苦的煎熬中慢慢死去。

Lesson 2 Hiroshima-the Liveliest City in Japan课文翻译

第二课 广岛——日本“最有活力”的城市 (节选) 雅各?丹瓦 ①“广岛到了!大家请下车!”当世界上 最快的高速列车减速驶进广岛车站并渐 渐停稳时,那位身着日本火车站站长制 服的男人口中喊出的一定是这样的话。 我其实并没有听懂他在说些什么,一是 因为他是用日语喊的。其次,则是因为 我当时心情沉重,喉咙哽噎,忧思万缕, 几乎顾不上去管那日本铁路官员说些什 么。踏上这块土地,呼吸着广岛的空气, 对我来说这行动本身已是一套令人激动 的经历,其意义远远超过我以往所进行的任何一次旅行或采访活动。难道我不就是在犯罪现场吗? ②这儿的日本人看来倒没有我这样的忧伤情绪。从车站外的人行道上看去,这儿的一切似乎都与日本其他城市没什么两样。身着和嘏的小姑娘和上了年纪的太太与西装打扮的少年和妇女摩肩接豫;神情严肃的男人们对周围的人群似乎视而不见,只顾着相互交淡,并不停地点头弯腰,互致问候:“多么阿里伽多戈扎伊马嘶。”还有人在使用杂货铺和烟草店门前挂着的小巧的红色电话通话。 ③“嗨!嗨!”出租汽车司机一看见旅客,就砰地打开车门,这样打着招呼。“嗨”,或者某个发音近似“嗨”的什么词,意思是“对”或“是”。“能送我到市政厅吗?”司机对着后视镜冲我一笑,又连声“嗨!”“嗨!”出租车穿过广岛市区狭窄的街巷全速奔驰,我们的身子随着司机手中方向盘的一次次急转而前俯后仰,东倒西歪。与此同时,这座曾惨遭劫难的城市的高楼大厦则一座座地从我们身边飞掠而过。 ④正当我开始觉得路程太长时,汽车嘎地一声停了下来,司机下车去向警察问路。就像东京的情形一样,广岛的出租车司机对他们所在的城市往往不太熟悉,但因为怕在外国人面前丢脸,却又从不肯承认这一点。无论乘客指定的目的地在哪里,他们都毫不犹豫地应承下来,根本不考虑自己要花多长时间才能找到目的地。

Hiroshima广岛 课文翻译

Hiroshima! Everybody off! ‖ That must be what the man in the Japanese stationmaster's uniform shouted, as the fastest train in the world slipped to a stop in Hiroshima Station. I did not understand what he was saying. First of all, because he was shouting in Japanese. And secondly, because I had a lump in my throat and a lot of sad thoughts on my mind that had little to do with anything a Nippon railways official might say. The very act of stepping on this soil, in breathing this air of Hiroshima, was for me a far greater adventure than any trip or any reportorial assignment I'd previously taken. Was I not at the scene of the crime?―广岛到了!大家请下 车!‖当世界上最快的高速列车减速驶进广岛车站并渐渐停稳时,那位身着日本火车站站长制服的男人口中喊出的一定是这样的话。我其实并没有听懂他在说些什么,一是因为他是用日语喊的,其次,则是因 为我当时心情沉重,喉咙哽噎,忧思万缕,几乎顾不上去管那日本铁路官员说些什么。踏上这块土地,呼吸着广岛的空气,对我来说这行动本身已是一套令人激动的经历,其意义远远超过我以往所进行的任 何一次旅行或采访活动。难道我不就是在犯罪现场吗? The Japanese crowd did not appear to have the same preoccupations that I had. From the sidewalk outside the station, things seemed mu ch the same as in other Japanese cities. Little girls and elderly ladies in kimonos rubbed shoulders with teenagers and women in western dress. Serious looking men spoke to one another as if they were obli vious of the crowds about them, and bobbed up and down re-heatedl y in little bows, as they exchanged the ritual formula of gratitude and respect: "Tomo aligato gozayimas." Oth ers were using little red telephones that hung on the facades of grocery stores and to bacco shops. 这儿的日本人看来倒没有我这样的忧伤情绪。从车站 外的人行道上看去,这儿的一切似乎都与日本其他城市没什么两样。 身着和嘏的小姑娘和上了年纪的太太与西装打扮的少年和妇女摩肩接豫;神情严肃的男人们对周围的人群似乎视而不见,只顾着相互交淡,并不停地点头弯腰,互致问候:―多么阿里伽多戈扎伊马嘶。‖还有 人在使用杂货铺和烟草店门前挂着的小巧的红色电话通话。 "Hi! Hi! " said the cab driver, whose door popped open at the very sig ht of a traveler. "Hi", or something that sounds very much li ke it, means "yes". "Can you take me to City Hall?" He grinne d at m e in the rear-view mirror and repeated "Hi!" "Hi! ‘ We

高级英语(1)第三版 Lesson 2 Hiroshima Paraphrase&Translation 答案

Paraphrase 1) Serious looking men spoke to one another as if they were oblivious of the crowds about them. (Para. 2) 2) At last this intermezzo came to an end, and I found myself in front of the gigantic City Hall. (Para. 5) 3) The rather arresting spectacle of little old Japan adrift amid beige concrete skyscrapers is the very symbol of the incessant struggle between the kimono and the miniskirt. (Para. 7) 4) I experienced a twinge of embarrassment at the prospect of meeting the mayor of Hiroshima in my socks. (Para. 8) 5) The few Americans and Germans seemed just as inhibited as I was. (Para. 10) 6) After three days in Japan, the spinal column becomes extraordinarily flexible. (Para. 12) 7) I was about to make my little bow of assent, when the meaning of these last words sank in, jolting me out of my sad reverie. (Para. 18) 8) … and nurses walked by carrying nickel-plated instruments, the very sight of which would send shivers down the spine of any healthy visitor. (Para. 28) 9) Because, thanks to it, I have the opportunity to improve my character. (Para. 38) 参考答案 1) Serious-looking men were so absorbed in their conversation that they seemed not to pay any attention to the people around them. 2) At last the taxi trip came to an end and I suddenly discovered that I was in front of the gigantic City Hall. 3) The traditional floating houses among high modern buildings represent the constant struggle between old tradition and new development./ The rather striking picture of traditional floating houses among high, modern buildings represents the constant struggle between traditional Japanese culture and the new, western style. 4) I suffered from a strong feeling of shame when I thought of the scene of meeting the mayor of Hiroshima wearing my socks only. 5) The few Americans and Germans seemed just as restrained as 1 was. 6) After three days in Japan one gets quite used to bowing to people as a ritual in greeting and to show gratitude. 7) I was on the point of showing my agreement by nodding when I suddenly realized what he meant.His words shocked me out my sad dreamy thinking. 8)… and nurses walked by carrying surgical instruments which were nickel plated and even healthy visitors when they see those instruments could not help shivering..

Hiroshima—the liveliest city in Japan

词汇(Vocabulary) reportorial ( adj.) :reporting 报道的,报告的 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------kimono ( n.) :a loose out garment with short,wide sleeve and a sash。part of the traditional costume of Japanese men and women 和服 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------preoccupation ( n.) :a matter which takes up an one's attention 令人全神贯注的事物 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------oblivious ( adj.) :forgetful or unmindful(usually with of or to)忘却的;健忘的(常与of 或to 连用) --------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------bob ( v.) :move or act in a bobbing manner,move suddenly or jerkily;to curtsy quickly 上下跳动,晃动;行屈膝礼 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------ritual ( adj.) : of or having the nature of,or done as a rite or rites 仪式的,典礼的 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------facade ( n.) :the front of a building;part of a building

Hiroshima JOHN HERSEY 英语读后感

After reading John Hersey’s book, Hiroshima, I feel very sympathetic towards the innocent citizens of that city in the 1940s. And it is the humanity’s most heinous crime, in my opinion. The behavior of six survivors in the atomic disaster is worthy of admiration in such an emergency. Among them there is one person who gives me a strong impression ——she is Mrs. Nakamura——a mother with three young children: a ten-year-old boy, an eight-year-old girl and a five-year-old girl. Her excellent virtue and qualities are the typical symbols of tender Japanese women in that contemporary society, which are also the spiritual wealth for us to learn from forever. Firstly, I amaze at Mrs. Nakamura’s courage and living belief of confronting the pain and misery continuous wars and the atomic bombardment brought to her. As we all know, her husband killed in the cruel battle of Singapore, the war made her become a widow and destroyed her happy family. Hearing this bad news, she must had been torn with grief, sorrow and depressed. However, although she suffered so much misfortune, she still kept calm and brought up the young children as usual, which may be one aim and one single purpose of the rest life of a mother, a Japanese mother. In order to support the whole family, she herself had to bear up the heavy burden. She, Mrs. Nakamura, got out the

Lesson 2 Hiroshima-the Liveliest City in Japan修辞学习

Hiroshima---the Liveliest City in Japan RHETORIC tenor (subject): the concept, object, or person meant in a metaphor vehicle (reference): a medium through which something is expressed, achieved, or displayed Simile: A simile makes a comparison between two unlike things having at least one quality or characteristic in common. The two things compared must be dissimilar and the basis of resemblance is usually an abstract quality. The vehicle is almost always introduced by the word "like" or "as". Self-criticism is as necessary to us as air or water. The water lay grey and wrinkled like an elephant's skin. My very thoughts were like the ghostly rustle of dead leaves. The bus went as slowly as a snail. Her eyes were jet black, and her hair was like a waterfall. The comparison is purely imaginative, that is, the resemblance between the two unlike things in that one particular aspect exists only in our minds, and not in the nature of the things themselves. As cold waters to a thirsty soul, so is good news from a far country. Metaphor: A metaphor, like a simile, also makes a comparison between two unlike things, but the comparison is implied rather than stated. Some say it the substitution of one thing for another, or the identification of two things from different ranges of thought. Contrary to a simile in which the resemblance between two unlike things is clearly stated, in a metaphor nothing is mentioned. It is often loosely defined as "an implied comparison", " a simile without 'like' or 'as'". Metaphor is considered the most important and basic poetic figure and also the commonest the most beautiful. Snow clothes the ground. The town was stormed after a long siege. Boys and girls, tumbling in the streets and playing, were moving jewels.

第二课 Hiroshima 词组总结 by miss chengyu

第二课Hiroshima 词组总结 1.slip to a stop 减速并渐渐停稳 2.Screech to a halt嘎地一声停下来 3.have a lump in one's throat 喉咙哽咽,哽咽欲泣 4.Be at the scene of the crime 在犯罪现场 Stand on the site of the first atomic bombardment置身在曾遭受第一颗原子弹袭击的现场 5.have the same preoccupations 有同样的心事 6.Rub shoulders with sb. /rub elbows with sb. informal AmE 与某人打交道 7.be oblivious of sth. 对某事全然没有觉察、毫不知情 8.Bob up and down点头弯腰 9.Exchange the ritual formula 互致客套话 10.Pop open 砰地打开 11.At the very sight of sth. 一看见某事物 12.grin at sb.满脸堆笑地看着某人 13.Set off at top speed全速行驶 14.The martyred city 惨遭劫难的城市 15.Flash by飞掠而过 16.Lurch from side to side 东倒西歪 17.Sharp twists of the wheel急打双向盘 18.Avoid loss of face 避免有损颜面

19.Without concern for sth.不计某事的后果 20.Heave a long sigh 长叹一口气 21.Sketch a map勾画出一张简易的地图 22.Arresting spectacle of sth. 引人注目的景观 23.The canal embankment 运河堤岸 24.Incessant struggle between 持续不断的斗争 25.A stunning,porcelain-faced woman一个面色如玉、极漂亮的女人 26.Remove one's shoes 脱鞋 27.The low-ceilinged rooms 低矮的房间 28.Tread on the tatami matting踏在榻榻米地席上 29.Experience a twinge of embarrassment at the prospect of sth. 想到某事时感到一阵尴尬 30.Be crushed by 非常伤心 31.Thousands upon thousands of people成千上万的人 32.Be slain in one second顷刻之间既遭毁灭 33.Linger on to die in slow agony在痛苦的煎熬中慢慢死去 34.The spinal column 脊椎骨 35.Be inhibited/agitated 局促不安 36.Gain world renown享誉全球 37.Sink in (消息、事实等)逐渐被充分理解 38.Jolt sb. out of sad reverie.使某人从忧愁伤感中惊醒

Something about Hiroshima广岛读后感

Something about 《Hiroshima》If American army did not throw the atomic bombs to Japan, the war would go on, and a huge damage would be made. But we couldn’t ignore the effect on Japanese. They suffered from physical and mental hurt. Their homes, their families, all the things they possessed that had lost in a short time. We all know that the atomic bomb explosion is powerful. The fact that they couldn’t avoid injuries and death.“This atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, as a direct result, some 60000 Japanese men, women, and children were killed, and 100000 injured; and almost the whole of a great seaport, a city of 250000 people, was destroyed by blast or by fire.” From this statistic, we can imagine how powerful atomic bomb is! As this small island nation, these mass casualties had been a huge blow. A hundred thousand people were killed by the atomic bomb, and fortunately, there were six survivors. This book introduced those six survivors’experiences. Of course, these experiences stick in their minds, nothing can erase these memories. There is a section of this book. “Mr. Tanimoto came

- 高级英语HIROSHIMA

- Hiroshima英文赏析

- Hiroshima广岛 课文翻译

- 高级英语(1)第三版 Lesson 2 Hiroshima Paraphrase&Translation 答案

- 第二课 Hiroshima 词组总结 by miss chengyu

- Lesson 2 Hiroshima-the Liveliest City in Japan课文翻译

- Lesson 2 Hiroshima-the Liveliest City in Japan课文翻译

- hiroshima__修辞赏析2

- 高级英语课件第一册第二课Hiroshima -- the Liveliest City in Japan

- Hiroshima(2010) ppt

- Hiroshima -- the Liveliest” city in Japan

- 完整word版,Lesson 2 Hiroshima-the Liveliest City in Japan课文翻译

- 高级英语第一册 Hiroshima— the “Liveliest” City in Japan

- Lesson 2 Hiroshima-the Liveliest City in Japan修辞学习

- Hiroshima-the liveliest city in the world翻译doc

- lesson 2 Hiroshima 高级英语第一册ppt课件

- Hiroshima的及物性过程分析

- Hiroshima—the liveliest city in Japan

- Something about Hiroshima广岛读后感

- 高级英语HIROSHIMA